Multi-continent field work with bilingual communities

Note: This case study will likely be of most interest to sociologists and/or quantitative folks, as it gets way in the weeds (this was my dissertation topic!) and does not have a UX focus.

What is code-switching and who does it?

Code-switching is when bilingual or bidialectal people use two or more languages (or dialects) in a conversation.

Code-switching is often stigmatized, but is a common communicative device in many communities. It also has many communicative functions, such as:

establishing solidarity,

efficiency, and

contextual appropriateness

When people code-switch, they can switch from Language A to Language B for just one word, entire sentences, or from one speaker to another.

Previous work on code-switching has been done primarily on the morphosyntax (word structure and order) of languages in contact with English.

Schematic example of code-switching: The switch can be insertional, like the person on the left or it can be more alternational, like the person on the right.

What happens when bilinguals code-switch between unrelated languages?

Specifically, what happens to the sound systems of these two languages during conversational code-switching?

Established work on morphosyntax showed evidence for a "Matrix Language Effect": That is, any differences in word structure or order between the two languages defaults to the patterns of the Matrix Language (the more dominant language of the conversation).

Would this effect carry over to differences in linguistic sounds systems as well?

To test this hypothesis, I wanted to look at naturalistic speech from two unrelated languages that are in high contact and have clear differences in their phonetic (sound) systems: Spanish and Basque.

Spain and the Basque Country

The Basque Country is an autonomous region in northern Spain where both Basque and Spanish have co-official status. Most people in the Basque Country are Spanish-Basque bilinguals.

Basque is a language isolate, meaning it is not related to any other language.

Spanish is an Indo-European language with many relatives, such as Portuguese, English, and German.

Spanish also has more socio-political power throughout Spain (including the Basque country).

In my study, I analyzed conversations from two regions in Bizkaia:

Bilbao, a metropolitan area that is Spanish-dominant

Lekeitio, a small town that is Basque-dominant

Since the Matrix Language makes reference to a dominant language in the interaction, I wanted to look at this both in terms of quantity (which language is used more in that interaction) and usage (which language is dominant in the speakers' lives).

A map of the Basque Autonomous Region in Spain. My study looked at two varieties of Basque in Bizkaia (Northwest region of the Basque Country).

Visualizing code-switching:

How do Spanish and Basque differ, sound-wise?

To investigate how sound differences between Spanish and Basque are resolved during code-switching, I needed to choose a trait that distinguishes them.

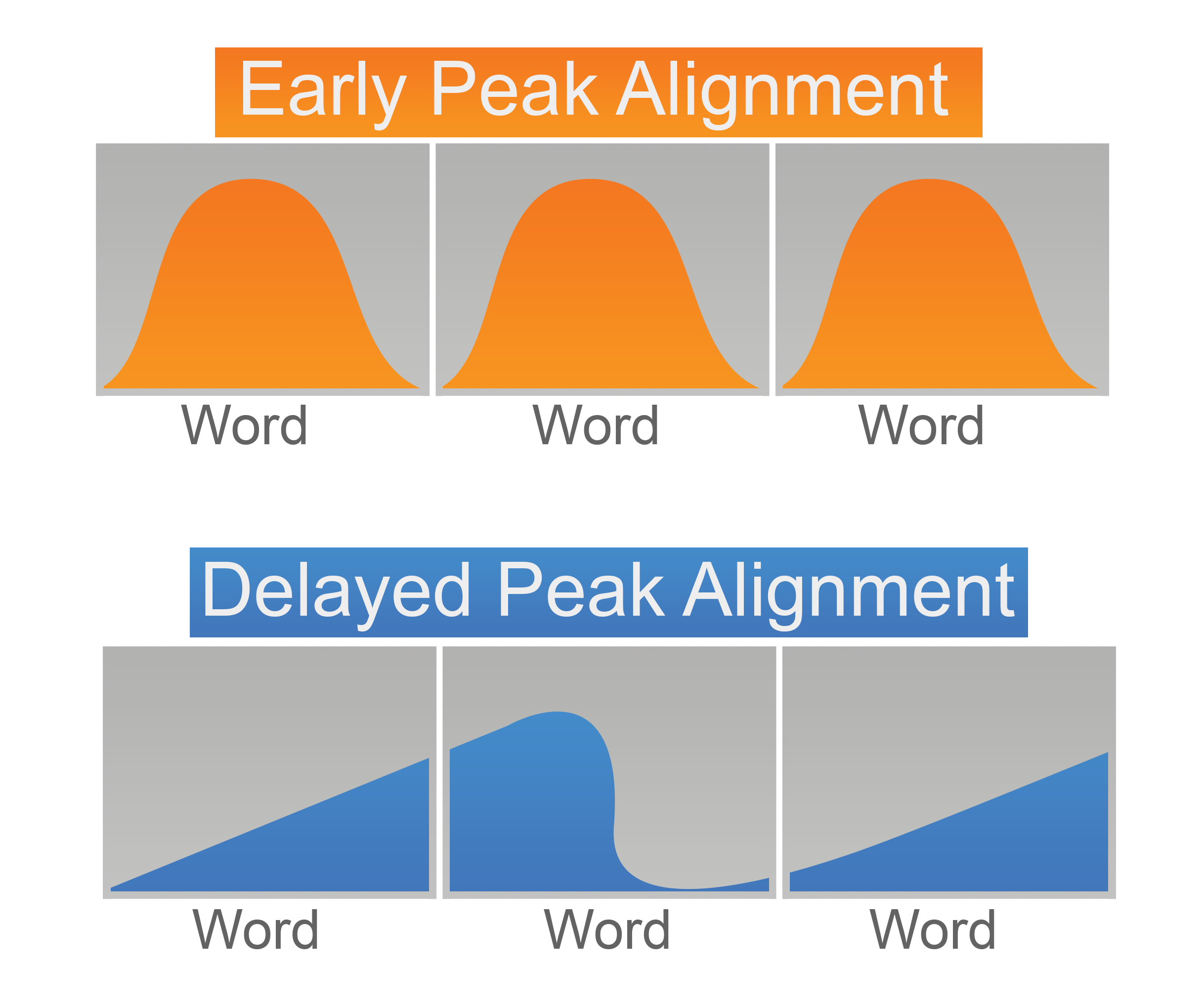

Both Spanish and Basque have stress in words that is marked by a rise in pitch. However, they differ by whether the peak of this rise is early or delayed in the word or syllable in question. For the language varieties references in this study, Basque has early peak alignment and Spanish has delayed peak alignment.

If the Matrix Language Hypothesis also applied to sound systems, we'd expect that in Spanish-dominant conversations, Basque words would have delayed peaks, and the reverse-in Basque-dominant conversations, Spanish words would have early peaks.

Examples of pitch peak alignment in Basque (early) and Spanish (delayed) based on this study's regional dialects.

This study's participants

Data Collection

Types of data collected

I needed to establish language dominance for each participant and also have samples of them speaking in Spanish and Basque.

To establish language dominance, participants completed a Semantic Verbal Fluency (SVF) task in which they named as many items as possible in each language for 8 categories

When people are being recorded, they are less likely to speak naturally at first. To assist with this, the speech tasks started in a more formal style and progress to more naturalistic

Task 1: Reading Task (in Spanish only)

Task 2: Discourse Completion Task (primarily in Spanish with Basque words to trigger code-switching)

This task presented participants with common scenarios and prompted them to respond in questions, exclamatives, and other categories

Task 3: Semi-structured interview (primarily in Basque, with interviewer code-switching to Spanish)

In this task, participants were asked about their lives and opinions on current events. The interviewer was instructed to code-switch so that participants also felt comfortable doing so

All speech tasks were administered by an in-group interviewer (female, 26) who is a native Spanish-Basque bilingual

Progression of speech tasks administered to participants

Evaluation:

Analyzing the factors that vary during code-switching

Categorizing language dominance and code-switches

Language Dominance

Continuous variable calculated by totaling responses for each language and dividing by number of categories answered, then dividing Basque score/Spanish score

Lower score = more Spanish-dominant; Higher score = less Spanish-dominant

Code-switches

All analyzable words were categorized as Spanish, Basque, or Ambiguous.

Ambiguous words were those which did not appear in one of 3 Basque dictionaries consulted

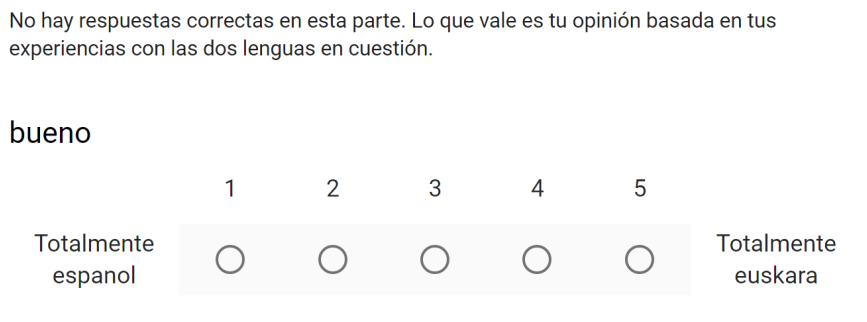

18 ambiguous words were placed in a survey (with 8 unambiguous distractors) in which 224 Spanish-Basque bilinguals were asked to rate on a 1-5 Likert scale whether a word was more Spanish or Basque-like

Words with an average score above 2.5 were eliminated

The data yielded 224 code-switched words and 824 non-switched words for analysis.

Example of Likert scale survey given to participants, in which they rated ambiguous words from 1 (totally Spanish) to 5 (totally Basque).

Translation: There are no correct answers for this part. What matters is your opinion based on your experiences with the two languages in question.

Statistical Analysis

Outlier removal: I used the Interquartile method, which is more resistant to skewed means due to atypically distributed data

This eliminated 6 code-switched words, for a total of 218 code-switches

Linear regression models were performed in R

Variance Inflation Factor used for multicollinearity, which eliminated 1 variable

Outcome variable: Peak alignment (in milliseconds)

Predictor variables:

Region (Bilbao, Lekeitio)

Context (Matrix or Embedded Language)

Prosodic Position (Medial, Final)

Social Language (at home, friends) (Spanish, Basque, Both)

Language Dominance (SVF) score (continuous variable)

Results

Research questions and results revisited

1. Is there support for the Matrix Language Hypothesis with phonetics (i.e. peak alignment in Basque and Spanish)?

The results showed support for the Matrix Language patterns overriding the Embedded Language in 3 out of 4 contexts tested (see Figure 1 below)

2. Does language dominance (regional and individual) interact with code-switched peak alignment production?

Yes to both!

When Spanish was the Matrix Language, speaker from Lekeitio (a Basque-dominant region) produced delayed peak alignment in Basque (early alignment expected; see Figure 2 below)

When Basque was the Matrix Language, all speakers produced Spanish with early peak alignment (delayed peak alignment expected, see Figure 3 below).

However, those not dominant in Basque (via individual Semantic Verbal Fluency scores) produced significantly later peak alignment in Spanish than speaker more dominant in Basque

Three figures describing the study's results. Charts were made in R using ggplot2.

These results validated previous observations and introduced new insights

Novel insights and limitations of this study

There were interactions between linguistic and social variables in the data, highlighting the links between factors such as region, individual language dominance, social language, and language structure when studying code-switching

The dominant language is more susceptible to deviations from expected norms when it is the embedded (i.e. code-switched) language. This suggests that it may be more difficult for speakers to maintain expected language norms in these contexts.

The Lekeitio group was more sensitive to Matrix Language Effects than the Bilbao group.

This may be an effect of the study's design, whose order privileged Spanish. The study started with Spanish (unilingual), progressed to Spanish as the matrix (with embedded Basque), and ended with Basque as the matrix (with embedded Spanish).

Code-switching from Basque into Spanish was more common than the reverse

Spanish has more socio-political power in Spain, and may serve as a default reference for code-switching (also referenced in work by linguist Hanna Lantto)

Additionally, most speakers in the Basque country are bilingual, but monolingual Basque speakers are extremely rare

This study had a small sample size (7 females) and limited dialect region (Bizkaia). Future study on this topic would benefit from a larger sample of speakers (including males and diverse age ranges) as well as broader dialect regions

Want to read about code-switching in more detail? Check out my dissertation for more information on Spanish-Basque code-switching or my book chapter on Spanish-English code-switching, which was the inspiration for my dissertation!